Posted In Economics, Market Analysis| 2 comments

Lets start by considering what futures contracts actually represent, and what backwardation and contango mean. (By the way, stick with me on this. It might seem a bit dry, but if you are new to trading futures contracts or commodity ETFs, It should vastly expand your knowledge in just 10 minutes). At the end I tie it together and explain how the forward curve is relevant to commodity speculators, investors, and traders.

Futures prices for commodities represent the supply and demand balance for a particular commodity contracted to deliver or sell at a future date. One of the clearest ways to view this is with a graph that displays what is called the forward curve. The forward curve is a graphical representation of the current price of each futures contract over a period of time. Here is an example:

The graph above displays the current price of each Natural Gas contract all the way out to the November 2016 contract. So, for example, if we look at the far right side of the graph, it looks like Nov. 2016 natural gas is priced at about $6.8/mmbtu.

This means that a user of natural gas (say a power company) can purchase a November 2016 contract at about this price and lock in the cost of his future natural gas purchases. A natural gas producer (such as the companies Williams (WMB) or Chesapeake (CHK) can also lock in their prices, though in their case they are locking in the price they are able to sell natural gas at in the future. This ability to “lock in” future prices of commodities allows both commodity producers and users to make rational decisions over time and to focus on their core businesses (Exploring an for energy or generating and distributing electricity)

Forward prices (as represented by futures contracts) play another critical role: They allow for the efficient allocation of scarce resources over time. How?

Lets think about the forward curve for a moment as it relates to a natural gas producer. At any given time, the producer (Lets create a fictional company named NAS Natural Gas Co.) has the option of either selling current natural gas production in the spot market, or of putting it in storage and selling it at a future date. How does the NAS Natural Gas Co. trader make this decision?

Well, the trader at NAS Nat Gas Co. knows how much it costs to store natural gas either because the company owns the storage facilities itself, or it is able to get a quote from a storage facility owner. He then takes this information and compares the cost of storage against the sale price he can lock in at different future contract maturity dates.

Lets say (for the sake of example) the price of the Natural Gas futures contract that expires in 6 months is $1.5 higher than the spot price, and the storage cost is equal to $.50 for the volume represented by one futures contract. In other words, the scheduler has found that by storing Natural Gas for six months, he can lock in an additional $10,000 revenue per contract on his sale of National Gas. (The NG futures contract is priced such that each $1 price increment is equal to $10,000).

The NAS Natural Gas Trader will compare this return to what is available in the spot market and to other futures contracts. If he finds that this is the most profitable option, he will make the trade. If the spot market proves to be the most profitable, he will not use a futures contract, but will rather just sell the current natural gas supply in the cash (immediate delivery) market. Much of this trading is done using swaps, however the basic principles are the same.

Now, WHY was the 6 month forward contract priced in a way that made it profitable for the NAS Natural Gas Co. to sell this contract? It is our example, so we will make up a reason:

In this case, it is because Peidmont Natural Gas (PNY) had a heavy need for gas six months from now (during the cold winter season), and had been bidding up the price. The Trader at NAS Natural Gas Co. has computer program that help him to analyze these types of arbitrage situations. Because NAS Nat Gas Co. has the benefit of very low storage costs, he was able to get to this trading opportunity ahead of other natural gas producers (Remember, this is just a simplified example to clarify the basic concepts).

There you have it. If you followed this example, you understand how forward prices work to effectively allocate scarce resources over time. Forward prices created an incentive for NAS Natural Gas Co. To sell their gas production at the moment in the future where it was most needed.

The demand for forward contracts and for storage in commodities such as natural gas is to a significant extent driven by seasonal patterns of production and consumption. One of the best resources for better understanding, tracking, and learning to profit from these seasonal patterns can be found here. (I am proud to have an affiliate agreement with this company, as I believe its services and research reports offer significant practical and educational value).

How does this all relate to commodity speculators, traders, and investors? There is good news: The slope of the forward curve gives price signals not just to commercial interests, but also to speculators. It can provide a strong clue as to whether a long or short position will (all else equal) be profitable in a given market.

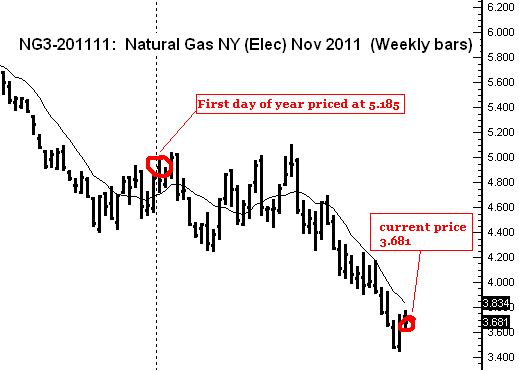

Lets look at a specific situation in Nat Gas over the past year. Here is a weekly price chart of Nov 2011 Natural Gas:

As you can see, the Nov 11 contract started the year at $5.185, and is currently at about 3.681, for a price decline of $1.324. This is equal to a loss of $13,340 per contract. How did the spot price perform during this time? Lets look at a price chart of the spot price:

The Natural Gas spot price started the year at 4.54, and is currently at 3.63. For a loss of $.91, or $9,100 per volume equivalent of one futures contract.

Notice that the November futures contract lost over $4,000 more (For an equal volume of Nat Gas) than the spot price over the same period of time! This was entirely do to the Decline in the forward premium as the contract approached its expiration date. This happens because as time passes, the futures price converges on the spot price. At the expiration date the “Futures” contract is no longer in the future, it is the present and therefore equal to the spot market.

In other words, if there is a significant premium in forward contracts and the spot price does not move at all, the futures contract will suffer a price decline equal to the forward premium.

Think about this for a minute. What it basically means is that if one sells short a contract in steep contango (contango is when forward prices are higher than the expected future spot price, and the curve slopes upward), the actual price of the underlying commodity does not even need to go down in order for the short seller to profit.

Lets look at the current market:

Currently, the Nat Gas spot price is about 3.63. Lets look at my quote board for the Nat Gas contract going out to March 2012:

Look at the Jan 12 Futures contract. It is currently selling for $3.923, or $.293 more than the current spot price. This means that if the spot price does not change at all from now until the January contract expires, the contract will lose $2,930 in value. Talk about a headwind for long positions!

Is there a catch? Yes, absolutely. The forward curve can and does change. Also, Any event that alters the supply/demand situation (such as a supply disruption or an unexpectedly cold winter) can send the price of the January 12 futures contract soaring. For this reason it is important for speculators to always have a planned risk limit on each and every trade. Basically, the speculator wants to get in and take advantage of the slope of the forward curve, while protecting himself from any adverse price spikes. In a sense it is not all that different from selling option premium (for those of you who are familiar with that concept).

An inverse situation applies when forward contracts are trading at a discount to the expected spot price. This is called backwardation. Research has demonstrated that most all of the net return generated by holding futures contracts long occurs in contracts that are trading at a discount to the spot price. The dynamics are exactly the same as in the above Natural Gas example, only in reverse.

Lets look at Sugar. The current spot price for Sugar #11 is 31.05. The march 2012 contract is priced at 27.66. (The Sugar #11 contract is priced such that each .01 = $11.20). This means that the March contract is priced at a 3.39 discount to spot. In other words, if the spot price does not move at all from now until this contract expires, the Contract will gain about $3,800 in value! That is quite a tail wind for any long positions, and provides a clue as to why research has demonstrated that any return earned from holding futures contracts (on average) occurs in markets that are in backwardation.

The bottom line:

Futures prices for commodities represent the supply and demand balance for a particular commodity contracted to deliver or sell at a future date. One of the clearest ways to view this is with a graph that displays what is called the forward curve. The forward curve is a graphical representation of the current price of each futures contract over a period of time. Here is an example:

The graph above displays the current price of each Natural Gas contract all the way out to the November 2016 contract. So, for example, if we look at the far right side of the graph, it looks like Nov. 2016 natural gas is priced at about $6.8/mmbtu.

This means that a user of natural gas (say a power company) can purchase a November 2016 contract at about this price and lock in the cost of his future natural gas purchases. A natural gas producer (such as the companies Williams (WMB) or Chesapeake (CHK) can also lock in their prices, though in their case they are locking in the price they are able to sell natural gas at in the future. This ability to “lock in” future prices of commodities allows both commodity producers and users to make rational decisions over time and to focus on their core businesses (Exploring an for energy or generating and distributing electricity)

Forward prices (as represented by futures contracts) play another critical role: They allow for the efficient allocation of scarce resources over time. How?

Lets think about the forward curve for a moment as it relates to a natural gas producer. At any given time, the producer (Lets create a fictional company named NAS Natural Gas Co.) has the option of either selling current natural gas production in the spot market, or of putting it in storage and selling it at a future date. How does the NAS Natural Gas Co. trader make this decision?

Well, the trader at NAS Nat Gas Co. knows how much it costs to store natural gas either because the company owns the storage facilities itself, or it is able to get a quote from a storage facility owner. He then takes this information and compares the cost of storage against the sale price he can lock in at different future contract maturity dates.

Lets say (for the sake of example) the price of the Natural Gas futures contract that expires in 6 months is $1.5 higher than the spot price, and the storage cost is equal to $.50 for the volume represented by one futures contract. In other words, the scheduler has found that by storing Natural Gas for six months, he can lock in an additional $10,000 revenue per contract on his sale of National Gas. (The NG futures contract is priced such that each $1 price increment is equal to $10,000).

The NAS Natural Gas Trader will compare this return to what is available in the spot market and to other futures contracts. If he finds that this is the most profitable option, he will make the trade. If the spot market proves to be the most profitable, he will not use a futures contract, but will rather just sell the current natural gas supply in the cash (immediate delivery) market. Much of this trading is done using swaps, however the basic principles are the same.

Now, WHY was the 6 month forward contract priced in a way that made it profitable for the NAS Natural Gas Co. to sell this contract? It is our example, so we will make up a reason:

In this case, it is because Peidmont Natural Gas (PNY) had a heavy need for gas six months from now (during the cold winter season), and had been bidding up the price. The Trader at NAS Natural Gas Co. has computer program that help him to analyze these types of arbitrage situations. Because NAS Nat Gas Co. has the benefit of very low storage costs, he was able to get to this trading opportunity ahead of other natural gas producers (Remember, this is just a simplified example to clarify the basic concepts).

There you have it. If you followed this example, you understand how forward prices work to effectively allocate scarce resources over time. Forward prices created an incentive for NAS Natural Gas Co. To sell their gas production at the moment in the future where it was most needed.

The demand for forward contracts and for storage in commodities such as natural gas is to a significant extent driven by seasonal patterns of production and consumption. One of the best resources for better understanding, tracking, and learning to profit from these seasonal patterns can be found here. (I am proud to have an affiliate agreement with this company, as I believe its services and research reports offer significant practical and educational value).

How does this all relate to commodity speculators, traders, and investors? There is good news: The slope of the forward curve gives price signals not just to commercial interests, but also to speculators. It can provide a strong clue as to whether a long or short position will (all else equal) be profitable in a given market.

Lets look at a specific situation in Nat Gas over the past year. Here is a weekly price chart of Nov 2011 Natural Gas:

As you can see, the Nov 11 contract started the year at $5.185, and is currently at about 3.681, for a price decline of $1.324. This is equal to a loss of $13,340 per contract. How did the spot price perform during this time? Lets look at a price chart of the spot price:

The Natural Gas spot price started the year at 4.54, and is currently at 3.63. For a loss of $.91, or $9,100 per volume equivalent of one futures contract.

Notice that the November futures contract lost over $4,000 more (For an equal volume of Nat Gas) than the spot price over the same period of time! This was entirely do to the Decline in the forward premium as the contract approached its expiration date. This happens because as time passes, the futures price converges on the spot price. At the expiration date the “Futures” contract is no longer in the future, it is the present and therefore equal to the spot market.

In other words, if there is a significant premium in forward contracts and the spot price does not move at all, the futures contract will suffer a price decline equal to the forward premium.

Think about this for a minute. What it basically means is that if one sells short a contract in steep contango (contango is when forward prices are higher than the expected future spot price, and the curve slopes upward), the actual price of the underlying commodity does not even need to go down in order for the short seller to profit.

Lets look at the current market:

Currently, the Nat Gas spot price is about 3.63. Lets look at my quote board for the Nat Gas contract going out to March 2012:

Look at the Jan 12 Futures contract. It is currently selling for $3.923, or $.293 more than the current spot price. This means that if the spot price does not change at all from now until the January contract expires, the contract will lose $2,930 in value. Talk about a headwind for long positions!

Is there a catch? Yes, absolutely. The forward curve can and does change. Also, Any event that alters the supply/demand situation (such as a supply disruption or an unexpectedly cold winter) can send the price of the January 12 futures contract soaring. For this reason it is important for speculators to always have a planned risk limit on each and every trade. Basically, the speculator wants to get in and take advantage of the slope of the forward curve, while protecting himself from any adverse price spikes. In a sense it is not all that different from selling option premium (for those of you who are familiar with that concept).

An inverse situation applies when forward contracts are trading at a discount to the expected spot price. This is called backwardation. Research has demonstrated that most all of the net return generated by holding futures contracts long occurs in contracts that are trading at a discount to the spot price. The dynamics are exactly the same as in the above Natural Gas example, only in reverse.

Lets look at Sugar. The current spot price for Sugar #11 is 31.05. The march 2012 contract is priced at 27.66. (The Sugar #11 contract is priced such that each .01 = $11.20). This means that the March contract is priced at a 3.39 discount to spot. In other words, if the spot price does not move at all from now until this contract expires, the Contract will gain about $3,800 in value! That is quite a tail wind for any long positions, and provides a clue as to why research has demonstrated that any return earned from holding futures contracts (on average) occurs in markets that are in backwardation.

The bottom line:

- Speculators should be biased towards long positions in contracts that are in steep backwardation, and short positions in contracts that are in steep contango.

- The forward curve should never be the only factor a trader looks at, however it is something worth studying and tracking in each market the trader is active in.

- ETF investors: DO NOT invest in commodity ETFs when the underlying commodity is in steep Contango! The negative roll yield can put a colossal headwind on any potential return. In fact, at times it can be so severe it almost seems that the losses are guaranteed. Just look at a long term price chart of VXX (VIX ETF) or UNG (Natural Gas ETF) to see how true this really is.

2 comments:

profit.biz

I read your post. That was amazing. Your thought processing is wonderful.

The way you tell the thing is awesome. They are inspiring and helpful.

Thank you.

Best Regards,

Gurleen Singh

Post a Comment