Summary

- US natural gas prices should remain low over the next few years, unless we're on the cusp of a new ice age.

- Associated gas production from liquids-rich plays continues

to grow, while increased drilling efficiency, process innovation and

improved completion techniques have enabled operators to extract more

gas from fewer rigs.

- An uptick in domestic demand and exports are still a ways off.

- Overlooked shadow capacity in the Haynesville Shale and

other plays will ensure that any meaningful increase in natural-gas

prices is short-lived.

Despite persistent weakness, pundits continue to call false

bottoms in natural gas prices and recommend shares of companies that

produce primarily natural gas.

Far too many investors and talking heads were head-faked

by the weather-driven spike in natural gas that occurred in early 2014,

buying shares of

Cabot Oil & Gas Corp (NYSE:

COG) and other names with sizable acreage positions in the

Marcellus Shale.

Here's why North American natural gas prices should remain low over the next two to three years.

Reason No. 1: US Natural Gas Production Remains Strong despite Low Prices

The

investment media made a big deal about last winter's upsurge in natural

gas prices, a phenomenon that stemmed from severely cold weather, not a

lasting change in the underlying supply and demand conditions.

Many

investors and media outlets focus on the spot market, where volumes are

available for immediate delivery. This price benchmark is much more

vulnerable to seasonal weather conditions.

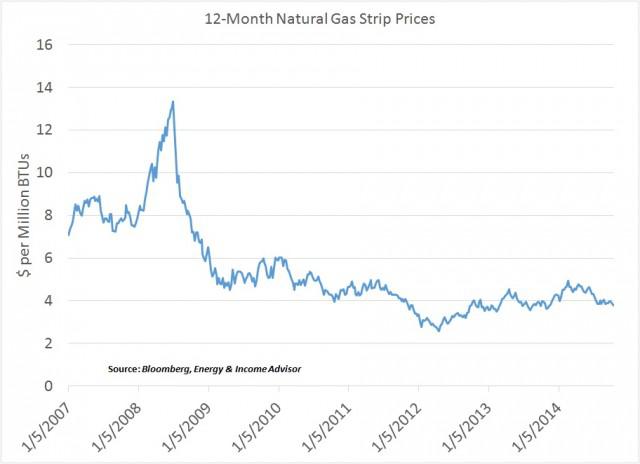

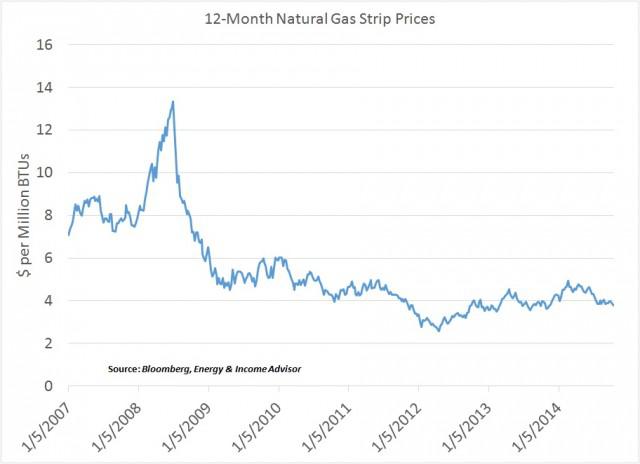

In contrast, oil and

gas producers focus on the 12-month strip, or the average cost of

natural gas for delivery over the next year. This forward-looking

benchmark

smoothes out weather-related fluctuations and other

temporary blips, providing better insight into the producer's full-year

price realizations.

On

this basis, North American natural gas prices have fluctuated around $4

per million British thermal units over the past four years, with the

high and low end of this range marked by the no-show 2011-12 winter and

the polar vortex earlier this year.

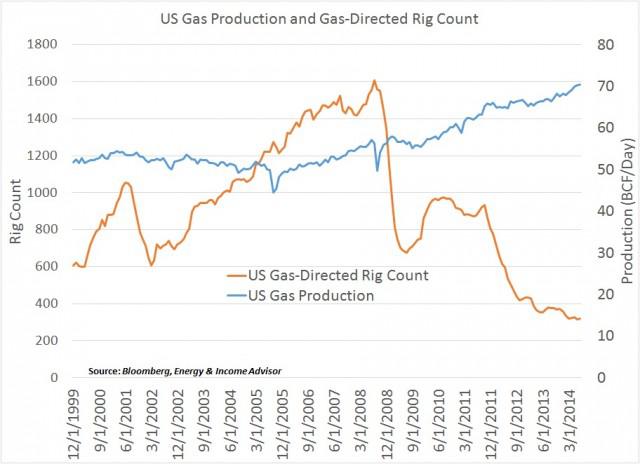

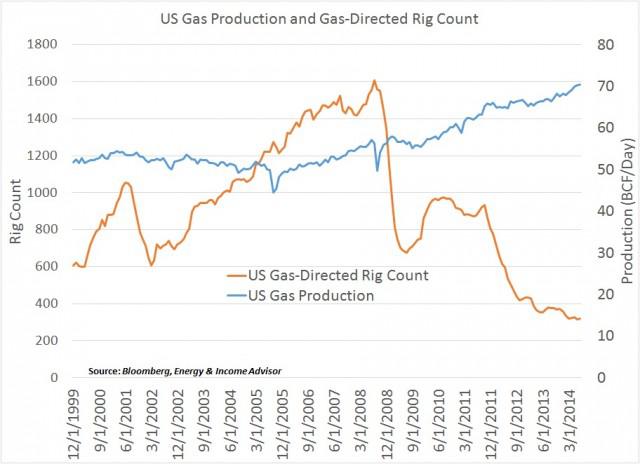

Plummeting natural gas prices

from mid-2008 to late 2009 prompted many upstream operators to scale

back drilling activity in the Haynesville Shale and other plays that

primarily produce this out-of-favor commodity.

However, the decline in gas-directed drilling activity hasn't resulted in a commensurate decline in US production.

Prior

the shale revolution, a decline in the number of active rigs targeting

natural gas would translate into lower production - exactly what

happened when drilling activity slumped from mid-2001 to mid-2002.

But the traditional relationship between the gas-directed rig count and production completely broke down in 2008.

Although

the number of rigs targeting natural gas collapsed from more than 1,600

in mid-2008 to 310 units in April 2014, US production has soared from

57 billion cubic feet per day to 70 billion cubic feet per day in July

2014.

This divergence reflects two factors:

Producers ramping up drilling activity in liquids-rich plays that also yield significant volumes of crude oil and

natural gas liquids; and

Huge gains in efficiency as producers hone their drilling and completion techniques and address supply-chain bottlenecks.

You can read more about these trends in

Breaking Down the US Onshore Rig Count and

Salute Your Drillmasters: Efficiency Gains Lower Production Costs.

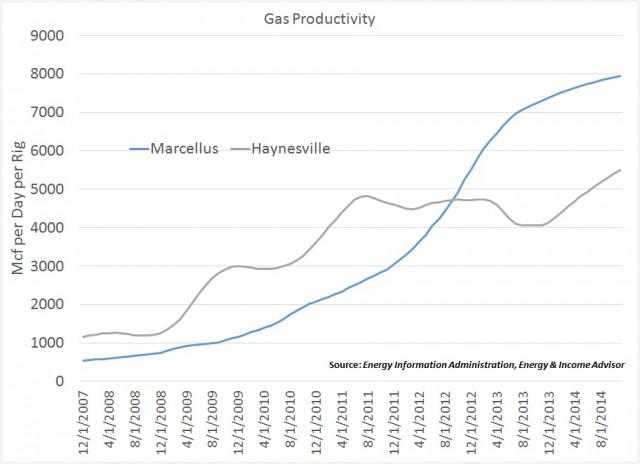

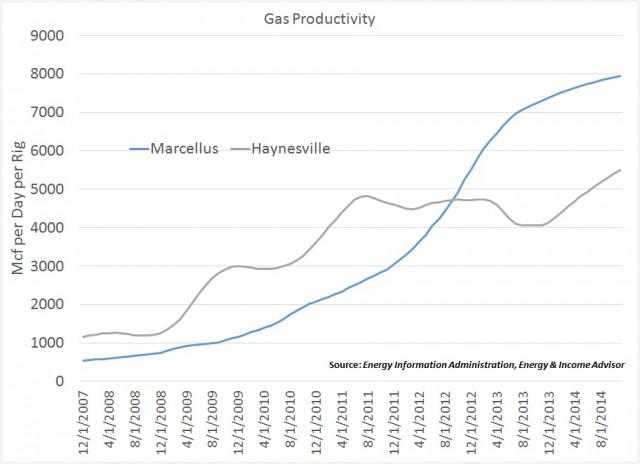

As

the energy industry has transitioned to pad drilling and optimized well

designs and completion techniques, operators have produced more natural

gas from fewer active rigs.

Over

the past two years, output per rig has increased by more than 50

percent in the Marcellus Shale, effectively lowering producers'

break-even costs to about $2 per million British thermal units in the

play's liquids-rich fairway.

Source:

Crestwood Midstream Partners LP

These

efficiency gains, coupled with readily available credit and independent

producers' imperative to grow their hydrocarbon output, mean that

natural-gas prices near $4 per million British thermal units are no

longer a disincentive to production.

But back in 2008, many

producers needed natural gas to fetch $7 to $8 per million British

thermal units to support drilling activity in higher-cost resource

plays.

In addition, 15 percent to 20 percent of US natural gas

production comes from oil wells, a figure that could increase in coming

years as more gas-gathering and processing infrastructure comes onstream

in the Bakken Shale.

Bottom Line: As long as crude oil remains above $70 per barrel, volumes of associated natural gas should continue to climb.

We

also expect North American crude-oil output to remain more resilient

than some expect because of hedging programs that lock in prices on

future output and independent producers allocating more capital to core

acreage that generates the best internal rates of return.

Reason No. 2: The Demand Response Won't Move the Needle Right Away

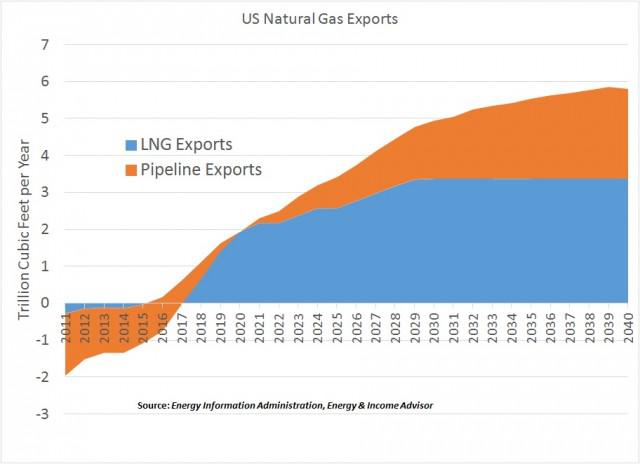

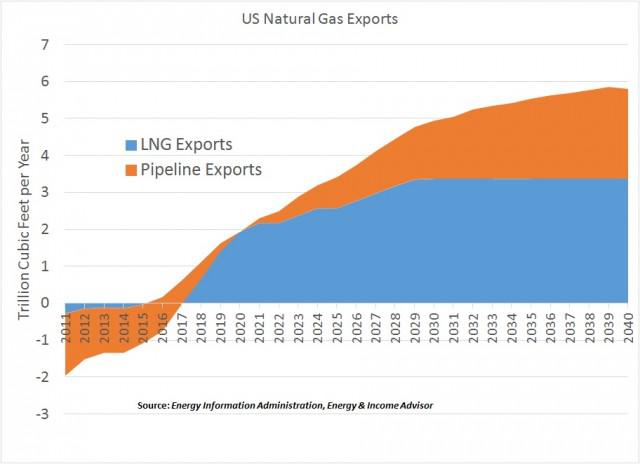

Over

the past few years, energy companies have proposed the construction of

more than 30 terminals to export liquefied natural gas (LNG). Thus far,

the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has approved only four

projects - about 6 billion cubic feet per day - to move forward.

But

the market itself will dictate how much LNG export capacity the US

adds; given the capital intensity of these projects, only terminals that

have secure volume commitments from customers will be able to obtain

the necessary financing. (See

Understanding the Appeal of US LNG Exports.)

The

case for LNG exports is deceptively simple: Whereas the 12-month strip

for US natural gas prices hovers around $3.60 per million British

thermal units, this commodity fetches $9 per million British thermal

units in Europe and $16 per million British thermal units in Asia.

When

you factor in the $6 to $7 per million British thermal units that it

would cost to liquefy and ship LNG from the Gulf Coast to Asia, these

price advantages appear slightly less compelling. Liquefaction and

shipping costs for cargoes headed to Europe are expected to range from

$3 to $4 per million British thermal units.

Cheniere Energy Partners LP's (NYSE:

CQP)

Sabine Pass facility is slated to start exporting LNG from the US Gulf

Coast in late 2015 or early 2016. More capacity will come onstream by

2020. By 2021, the US will also export more natural gas to Mexico and

Canada via pipeline than it imports.

All told, the Energy

Information Administration (EIA) forecasts that the US will export about

2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas annually by 2020 - about 7 percent

of projected supplies.

The

EIA's longer-term outlook contemplates the US exporting 5.8 trillion

cubic feet of natural gas per year and 37.5 trillion cubic feet in

annual production. Although long-range projections in the energy patch

should be taken with a grain of salt, US exports would account for only

15 percent of domestic output in this scenario.

And if US natural

gas prices were to rally temporarily, the price advantage for customers

in Asia and Europe would diminish, eroding demand in the international

spot market.

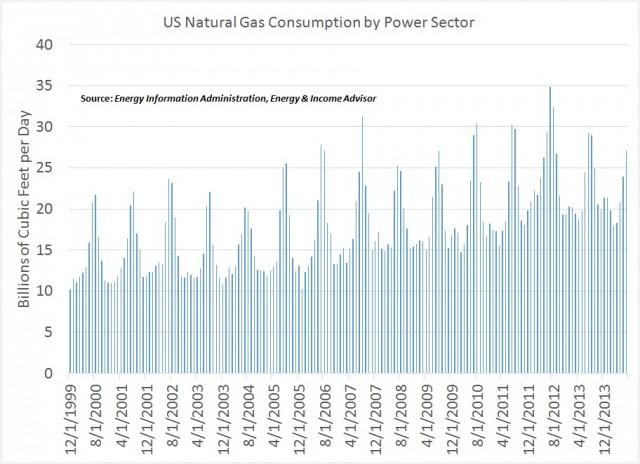

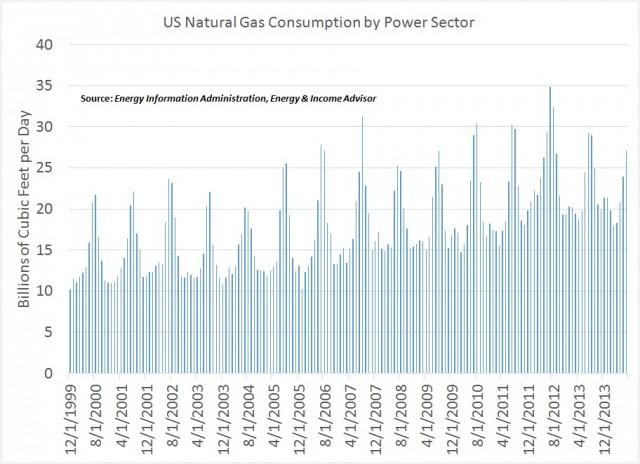

Commentators who predict a surge in natural gas

demand from electric utilities likewise overlook the scope that power

producers have to switch between coal and natural gas at their plants,

depending on which thermal fuel offers the best economics.

Natural gas consumption in the power sector spiked in 2012 after the no-show winter depressed the price of this commodity.

But

electric utilities have reduced their natural gas consumption over the

past two years. In July 2014, the power sector burned about 7.8 billion

cubic feet per day of natural gas less than in 2012.

The

catalysts for this trend: Depressed coal prices and natural gas prices

that remained elevated after the severely cold 2013-14 winter, a

situation that incentivized electric utilities to switch fuels.

In

July 2014, US electricity demand fell 2.3 percent year over year

because of a more than 12 percent drop in total cooling degree day.

Natural gas consumption in the power sector tumbled 7.3 percent, while

coal demand dropped 1.9 percent.

Stricter regulation of carbon

dioxide emissions will lead to the shutdown of as much as 50 to 60

gigawatts of coal-fired generation capacity in the US-roughly 15 percent

to 20 percent of the current fleet. About 30 gigawatts could be

shuttered by the end of next year.

Although the anticipated

reduction in coal-fired capacity will be offset by an increased reliance

on natural gas, the 1 trillion cubic feet per annum in incremental

demand that's expected to materialize by 2020 won't offset a 4.5

trillion cubic feet jump in annual production.

Reason No. 3: Overlooked Shadow Capacity

In

the global crude-oil market, analysts pay close attention to OPEC's

spare production capacity, or oil fields that could ramp up output

quickly to offset a supply outage and rebalance the market.

Saudi

Arabia controls much of this spare capacity and stepped up its output in

2011 to dampen the Libyan civil war's effect on global oil prices.

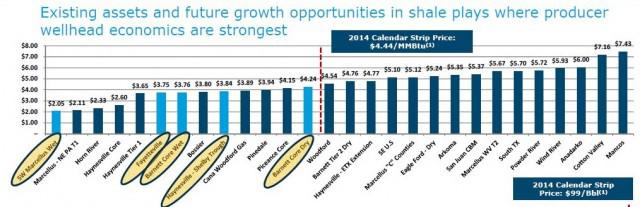

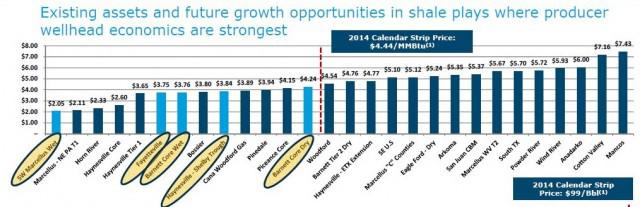

Similarly,

North America boasts a number of prolific natural gas plays in which

producers could accelerate drilling activity if prices were to climb to

between $4.50 and $5 per million British thermal units.

Based on

total reserves, Louisiana's Haynesville Shale is one of the largest gas

plays in the US. However, this play has fallen out of favor because it

produces negligible volumes of crude oil and natural gas liquids,

higher-priced hydrocarbons that help to boost economics.

This

unfavorable production mix explains why drilling activity in the

Haynesville Shale slumped sharply after 2008 and gas production from

this field had plummeted by almost one-third from its peak.

However,

the Haynesville Shale's rig count and production levels appear to have

bottomed last winter, suggesting that natural gas prices over $4.50 per

million British thermal units would incentivize producers to accelerate

drilling activity in the play's core region.

Most analysts

estimate that natural gas prices of $5 per million British thermal units

would enable producers to make money in the marginal portions of the

Haynesville Shale.

The region already boasts sufficient pipeline

and processing capacity to handle an increase in production, while its

proximity to proposed export capacity on the Gulf Coast is another plus.

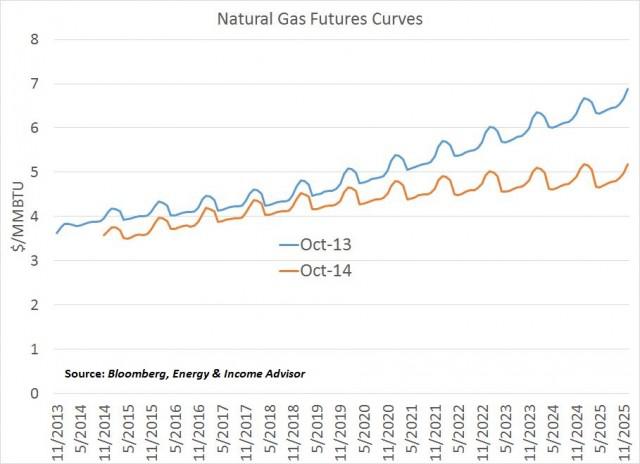

In

short, any sustained upsurge in North American natural-gas prices would

be stymied by an influx of output from the Haynesville Shale and other

plays.

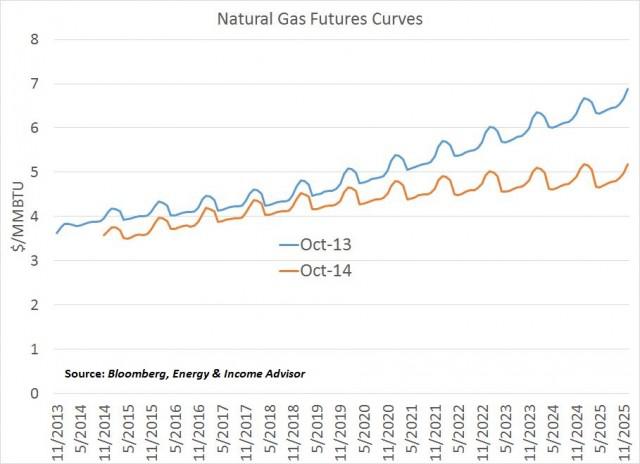

The current natural gas futures curve projects that prices

generally will remain below $5 per million British thermal through at

least the middle of the coming decade.

Futures

market expectations for gas prices are lower today than they were a

year ago; the rapid build in inventories has convinced the market that

significant structural changes will need to take place to tighten the

supply-demand balance for more than a month or two.

2200

2200